Neuroplasticity reveals the brain’s remarkable capacity for lifelong reorganization, forming new connections and adapting to experiences—a concept explored deeply within the PDF.

Overview of Neuroplasticity

Neuroplasticity, fundamentally, is the brain’s extraordinary ability to reshape itself by forging new neural connections throughout an individual’s lifespan. This dynamic process isn’t limited to childhood; it continues into adulthood, allowing adaptation to learning, new experiences, and even recovery from neurological injuries – a core theme within “The Brain That Changes Itself” PDF.

It encompasses several key mechanisms, including synaptic plasticity (strengthening or weakening connections), structural plasticity (physical changes to the brain’s architecture), neurogenesis (the birth of new neurons), and functional reorganization (remapping brain functions to different areas). The PDF details how these processes enable the brain to compensate for damage and optimize performance. Understanding neuroplasticity is crucial for advancements in neurorehabilitation, education, and mental health interventions, offering hope for improved outcomes and a deeper understanding of the brain’s potential.

The Significance of Norman Doidge’s Work

Norman Doidge’s “The Brain That Changes Itself” – readily available as a PDF – profoundly impacted public and scientific understanding of neuroplasticity. Before his work, traditional neuroscience largely adhered to the belief that the brain was largely fixed after childhood. Doidge’s compelling case studies demonstrated the brain’s remarkable capacity for change, even in adulthood, challenging this long-held dogma.

He meticulously documented instances of individuals overcoming seemingly insurmountable neurological challenges through targeted interventions, highlighting the brain’s inherent ability to rewire itself. The PDF showcases stories of stroke recovery, phantom limb pain relief, and improvements in learning disabilities, all attributed to harnessing neuroplasticity. Doidge’s accessible writing style brought complex scientific concepts to a wider audience, fostering hope and inspiring new avenues of research and therapeutic approaches.

Historical Context: Challenging Traditional Neuroscience

For decades, the prevailing view in neuroscience, prior to the widespread availability of resources like “The Brain That Changes Itself” in PDF format, posited a largely static brain. The dominant belief was that brain structure was primarily determined early in life, with limited capacity for significant alteration. This perspective stemmed from early neurological observations and a lack of tools to observe the brain’s dynamic processes.

However, emerging research in the mid-20th century, including advances in intracellular recordings and patch-clamp techniques, began to reveal evidence of synaptic plasticity – the strengthening and weakening of connections. Doidge’s work, popularized through his book and accessible PDF versions, synthesized these findings and presented compelling clinical examples, directly challenging the notion of a fixed brain and ushering in a new era of neuroplasticity research.

Core Principles of Brain Plasticity

Synaptic plasticity, structural changes, neurogenesis, and functional reorganization are key mechanisms detailed in “The Brain That Changes Itself” PDF.

Synaptic Plasticity: Strengthening & Weakening Connections

Synaptic plasticity, a cornerstone of neuroplasticity detailed in “The Brain That Changes Itself” PDF, fundamentally alters the strength of connections between neurons. This dynamic process, occurring through long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD), allows the brain to reinforce frequently used pathways and prune those less utilized.

LTP strengthens synaptic connections, enhancing signal transmission, while LTD weakens them, diminishing signal flow. These changes aren’t merely structural; they involve alterations in receptor numbers and synaptic morphology. Experiences, learning, and even injury trigger these modifications, shaping neural networks. The PDF emphasizes how this constant refinement allows for adaptation and skill acquisition.

Essentially, synapses aren’t fixed; they’re malleable, responding to activity and contributing to the brain’s remarkable ability to reorganize itself throughout life. This foundational principle underpins many of the remarkable recoveries and adaptations documented in Doidge’s work.

Structural Plasticity: Physical Changes in the Brain

Structural plasticity, as illuminated in “The Brain That Changes Itself” PDF, goes beyond synaptic adjustments, involving tangible physical alterations within the brain’s architecture. This encompasses changes in cortical thickness, grey matter volume, and even the formation of new blood vessels – angiogenesis – to support increased neural activity.

The brain isn’t static; it remodels itself, growing new dendritic spines (the receiving ends of neurons) and retracting others based on experience. Prolonged learning or intensive rehabilitation can demonstrably increase grey matter density in relevant brain regions. Conversely, disuse can lead to cortical shrinkage.

The PDF highlights that these structural changes aren’t limited to development; they occur throughout adulthood, demonstrating the brain’s continuous capacity for adaptation. This physical remodeling is crucial for recovery from injury and the acquisition of new skills, showcasing the brain’s inherent resilience.

Neurogenesis: The Birth of New Neurons

Neurogenesis, the creation of new neurons, was once believed to be limited to early brain development, but “The Brain That Changes Itself” PDF details groundbreaking research proving it continues in adult brains, particularly in the hippocampus (crucial for learning and memory) and the subventricular zone. This challenges long-held neurological dogma.

While the rate of adult neurogenesis is relatively slow, it’s significantly influenced by experience and environment. Factors like learning, exercise, and enriched environments can stimulate the birth of new neurons, enhancing cognitive function. Conversely, stress and depression can suppress neurogenesis.

The PDF emphasizes that these newly formed neurons aren’t simply added randomly; they integrate into existing neural circuits, contributing to plasticity and potentially aiding in recovery from brain injury. This ongoing neuronal replenishment underscores the brain’s remarkable regenerative capacity.

Functional Reorganization: Mapping Brain Functions

Functional reorganization, as detailed in “The Brain That Changes Itself” PDF, describes the brain’s ability to redistribute functions from damaged areas to undamaged ones. This isn’t a simple transfer; it involves a complex rewiring of neural pathways, demonstrating the brain’s dynamic mapping capabilities.

Traditionally, neuroscience held a rigid view of brain mapping – specific areas dedicated to specific functions. However, the PDF showcases cases where, following injury, other brain regions take over lost functions, proving this map isn’t fixed. This plasticity allows for remarkable recovery.

The extent of reorganization depends on factors like the injury’s severity, the individual’s age, and the intensity of rehabilitation. The PDF highlights how targeted therapies can actively promote this process, guiding the brain to remap functions effectively, showcasing the brain’s adaptability.

Factors Influencing Brain Plasticity

“The Brain That Changes Itself” PDF details how age, learning, environment, and injury significantly impact the brain’s capacity for plasticity and adaptation.

Age & Critical Periods

“The Brain That Changes Itself” PDF emphasizes that while neuroplasticity occurs throughout life, its degree varies with age. Early brain development features heightened plasticity, establishing critical periods – windows of time optimal for specific skill acquisition, like language.

During these periods, the brain is exceptionally sensitive to environmental input, readily forming and refining neural connections. However, plasticity doesn’t cease after these windows; the brain retains the ability to reorganize, albeit often requiring more effort. The PDF illustrates how interventions are most effective when aligned with these developmental stages.

Furthermore, the document suggests that understanding these age-related differences is crucial for tailoring rehabilitation strategies and educational approaches, maximizing the potential for positive change across the lifespan. The brain’s adaptability, though dynamic, is demonstrably influenced by the timing of experiences.

Learning & Experience

“The Brain That Changes Itself” PDF profoundly demonstrates that learning and experience are primary drivers of neuroplasticity. Every new skill acquired, every memory formed, and every experience encountered physically alters the brain’s structure and function. This isn’t merely metaphorical; synaptic connections strengthen with repeated use, while unused connections weaken – a principle known as synaptic pruning.

The PDF highlights how actively engaging with the environment fosters greater plasticity. Challenging tasks, novel experiences, and deliberate practice all contribute to the brain’s ongoing remodeling. This continuous adaptation allows us to refine existing abilities and acquire new ones throughout life.

Essentially, the brain is shaped by what we do, think, and feel, reinforcing the idea that we have the power to influence our own neural pathways and cognitive capabilities. The document underscores the brain’s remarkable responsiveness to experience.

Environmental Enrichment

“The Brain That Changes Itself” PDF emphasizes the crucial role of environmental enrichment in maximizing brain plasticity. A stimulating environment – rich in sensory input, opportunities for social interaction, and cognitive challenges – profoundly impacts neural development and function. This isn’t limited to early childhood; benefits extend throughout the lifespan.

The PDF details how enriched environments promote neurogenesis, the birth of new neurons, particularly in the hippocampus, a brain region vital for learning and memory. Increased synaptic density and enhanced neuronal connections are also observed. Essentially, a complex and engaging environment ‘exercises’ the brain, fostering its adaptability.

Conversely, impoverished environments can hinder plasticity and even lead to neural atrophy. The document powerfully illustrates that the brain thrives on stimulation and interaction, underscoring the importance of creating supportive and enriching surroundings.

Injury & Neurorehabilitation

“The Brain That Changes Itself” PDF powerfully demonstrates that brain injury doesn’t necessarily equate to permanent loss of function. Neuroplasticity offers a pathway to recovery, as the brain can reorganize itself to compensate for damaged areas. This is the core principle behind neurorehabilitation.

The PDF highlights cases where individuals regained abilities after stroke or traumatic brain injury, not through regrowth of damaged tissue, but through the brain rerouting functions to intact regions. Intensive, targeted therapy – forcing the brain to adapt – is key to this process. Constraint-induced movement therapy, for example, encourages use of a weakened limb.

The document stresses that the brain’s capacity for change exists even after significant injury, offering hope and a scientific basis for effective rehabilitation strategies. Understanding plasticity is paramount for maximizing recovery potential.

Applications of Brain Plasticity

“The Brain That Changes Itself” PDF reveals plasticity’s potential in stroke recovery, learning disabilities, mental health, and overcoming phantom limb pain through targeted interventions.

Stroke Recovery & Rehabilitation Techniques

“The Brain That Changes Itself” PDF profoundly illustrates how neuroplasticity fuels stroke recovery, challenging the long-held belief in fixed brain damage. Following a stroke, the brain can remap functions from damaged areas to healthy ones, enabling regained movement, speech, and cognitive abilities.

Rehabilitation techniques, like constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT), force patients to use the affected limb, stimulating neural reorganization. Similarly, intensive task-specific training focuses on repetitive practice of essential movements, strengthening relevant pathways. Mirror therapy, detailed within the PDF, leverages visual feedback to ‘trick’ the brain into believing movement is occurring, aiding motor recovery.

These approaches aren’t merely about compensation; they actively promote genuine neural change. The PDF emphasizes that the brain’s capacity for plasticity is greatest immediately post-stroke, highlighting the critical importance of early and intensive rehabilitation. Understanding these principles empowers both therapists and patients in maximizing recovery potential.

Treating Learning Disabilities

“The Brain That Changes Itself” PDF demonstrates how neuroplasticity offers innovative approaches to learning disabilities, moving beyond traditional remedial methods; Dyslexia, dysgraphia, and other challenges aren’t viewed as fixed deficits, but as differences in neural organization that can be reshaped through targeted interventions.

Techniques like intensive phonological training for dyslexia aim to strengthen the neural pathways responsible for sound-letter correspondence. Similarly, programs focusing on visual processing skills can aid individuals with visual-spatial learning difficulties. The PDF highlights the importance of multi-sensory learning, engaging multiple brain areas simultaneously to enhance neural connections.

Crucially, these interventions aren’t simply about memorization; they aim to fundamentally alter brain function. The PDF underscores that plasticity is maximized with focused, repetitive practice and personalized approaches, tailoring interventions to individual neural profiles and fostering lasting improvements in learning abilities.

Mental Health Interventions (e.g., PTSD, Depression)

“The Brain That Changes Itself” PDF reveals how neuroplasticity is revolutionizing mental health treatment, offering hope for conditions like PTSD and depression. These disorders often involve altered neural circuitry – for example, overactive amygdala in PTSD or reduced hippocampal volume in depression – which can be targeted through plasticity-based therapies.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), a cornerstone of mental health care, leverages plasticity by helping patients reshape negative thought patterns and behaviors, strengthening alternative neural pathways. Exposure therapy for PTSD aims to extinguish fear responses by repeatedly activating and then safely resolving traumatic memories, altering amygdala function.

The PDF emphasizes that interventions aren’t just about symptom management; they’re about fostering genuine neural change. Mindfulness practices and neurofeedback also demonstrate potential, promoting self-regulation and optimizing brain activity, ultimately leading to lasting improvements in mental wellbeing.

Phantom Limb Pain & Mirror Therapy

“The Brain That Changes Itself” PDF presents a compelling case study in phantom limb pain, illustrating how the brain’s map of the body can become distorted after amputation. The brain continues to receive signals from the missing limb, often interpreting them as pain due to maladaptive plasticity within the somatosensory cortex.

Mirror therapy, a groundbreaking intervention detailed in the PDF, exploits this plasticity. By visually associating movements of the intact limb with the reflected image, patients create the illusion of movement in the phantom limb, effectively “rewiring” the brain and reducing pain signals.

This technique demonstrates the brain’s remarkable ability to reorganize itself, even in the absence of physical input. The PDF highlights that mirror therapy isn’t a cure, but a powerful tool for retraining the brain and alleviating chronic pain, showcasing the potential of harnessing neuroplasticity for restorative purposes.

“The Brain That Changes Itself” ⏤ Key Case Studies

The PDF details transformative stories—sight regained, brains compensating for loss, and music’s impact—demonstrating neuroplasticity’s power to reshape neurological function and recovery.

The Case of the Woman Who Regained Sight

The PDF presents a compelling case study of a woman who, after decades of blindness, remarkably regained functional vision through intensive visual training. Her brain, deprived of visual input for years, hadn’t simply forgotten how to “see,” but lacked the established neural pathways.

Through dedicated therapy, she relearned to interpret visual information, demonstrating the brain’s astonishing plasticity. This wasn’t a restoration of perfect sight, but a rewiring of brain areas to process visual stimuli, utilizing previously untapped potential. The case highlights how the brain can reorganize itself even after prolonged sensory deprivation, challenging traditional views of neurological limitations.

This remarkable recovery underscores neuroplasticity’s capacity to create new connections and repurpose existing brain regions, proving that the brain isn’t fixed but dynamically adaptable throughout life, as detailed within the document.

The Man with Half a Brain

The PDF details the extraordinary story of a man who underwent a hemispherectomy – the removal of half his brain – yet continued to function remarkably well. Initially, this seemed impossible, given the conventional understanding of brain localization. However, his case vividly illustrates the brain’s capacity for dramatic functional reorganization.

Following the surgery, the remaining hemisphere took over many of the functions previously handled by the removed portion. This wasn’t simply a matter of redundancy; the brain actively remapped and repurposed its resources, demonstrating incredible plasticity. The document emphasizes that the young age at which the surgery occurred was crucial, allowing for greater adaptability.

This case powerfully demonstrates that the brain isn’t rigidly structured, but possesses a remarkable ability to compensate and rewire itself, even after such a profound loss, as thoroughly explored within the PDF’s analysis.

The Impact of Music Therapy on Brain Function

The PDF showcases compelling evidence of music therapy’s profound impact on brain plasticity, particularly in individuals recovering from neurological injuries or conditions. Music isn’t merely an auditory experience; it actively engages multiple brain regions simultaneously, fostering neural connections and promoting functional recovery.

Case studies detailed within the document reveal how musical training and active listening can enhance motor skills, speech, and cognitive function. The brain’s ability to remap functions allows undamaged areas to compensate for those affected by injury, and music serves as a powerful catalyst for this process.

Furthermore, the PDF highlights how music can evoke emotional responses, triggering neurochemical changes that support learning and rehabilitation. This demonstrates the brain’s holistic response to stimuli, reinforcing its capacity for change and adaptation, as meticulously documented.

Limitations & Future Research

The PDF acknowledges the complexity of brain mapping and individual variability in plasticity, urging further research into ethical considerations and nuanced understanding.

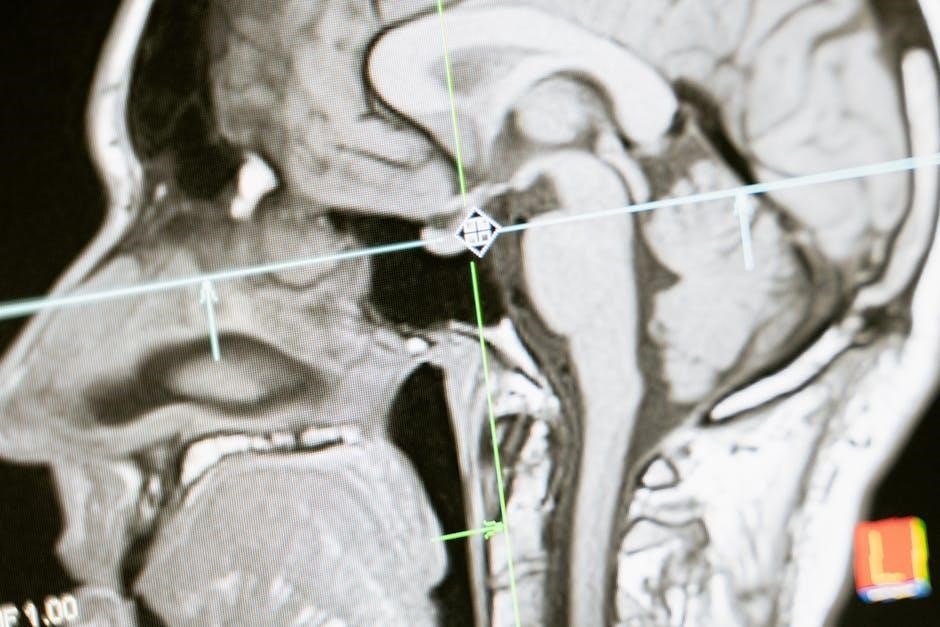

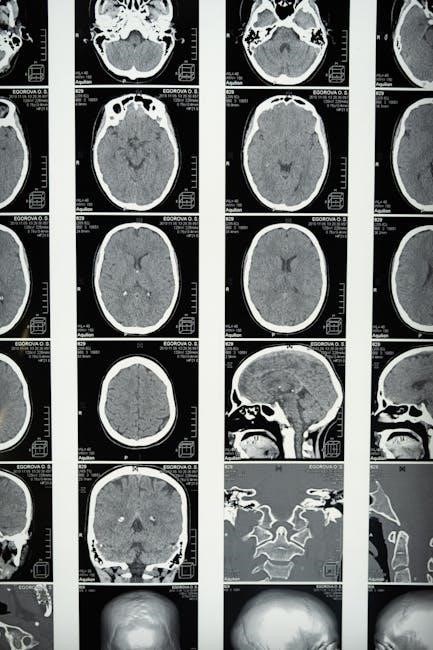

The Complexity of Brain Mapping

Brain mapping, as discussed within “The Brain That Changes Itself” PDF, presents significant challenges due to the brain’s dynamic and individualized nature. Traditional methods often struggle to capture the full extent of neuroplastic changes, particularly the subtle shifts in functional organization. The brain isn’t a static entity; it constantly remodels itself, making precise localization of functions a moving target.

Furthermore, individual variability plays a crucial role. Each brain exhibits unique structural and functional characteristics, influenced by genetics, experiences, and learning. What holds true for one individual may not generalize to another, complicating efforts to create universal brain maps. Advanced neuroimaging techniques, while improving resolution, still offer incomplete pictures of the intricate neural networks at play.

The PDF highlights that understanding plasticity requires moving beyond simply identifying where functions reside to understanding how they adapt and reorganize over time, a far more complex undertaking.

Individual Variability in Plasticity

“The Brain That Changes Itself” PDF emphasizes that neuroplasticity isn’t a uniform process; individuals demonstrate vastly different capacities for brain reorganization. Genetic predispositions, early life experiences, and pre-existing neurological conditions all contribute to this variability. Some brains exhibit remarkable resilience and adaptability, while others show limited responsiveness to interventions.

Factors like age, overall health, and motivation also play significant roles. The PDF details cases where similar injuries resulted in drastically different recovery trajectories, highlighting the influence of individual factors. This underscores the need for personalized approaches to neurorehabilitation and therapeutic interventions.

Understanding these differences is crucial for predicting treatment outcomes and tailoring strategies to maximize individual potential. A one-size-fits-all approach to harnessing plasticity is unlikely to be effective, given the inherent uniqueness of each brain.

Ethical Considerations in Neuroplasticity Research

“The Brain That Changes Itself” PDF implicitly raises several ethical concerns as our understanding of neuroplasticity deepens. The potential to intentionally manipulate brain function, while promising for therapeutic interventions, also carries risks of misuse. Questions arise regarding cognitive enhancement, personality alteration, and the potential for coercion.

Research involving vulnerable populations – such as individuals with brain injuries or mental health conditions – demands particularly careful consideration of informed consent and potential harms. The PDF suggests a need for robust ethical guidelines to govern the development and application of neuroplasticity-based technologies.

Furthermore, equitable access to these advancements is a critical concern. Ensuring that the benefits of neuroplasticity research are available to all, and not just the privileged, is essential for promoting social justice and minimizing disparities in healthcare.